As a postgraduate student studying Book History and Material Culture at the University of Edinburgh, I have been lucky enough to receive full access to the museum’s special book collection – consisting of children’s literature printed and published prior to 1850 – in order to update the catalog with information about its contents. While working through the books, I’ve noticed a few trends that seem to reflect the history of children’s literature in general.

The first, and most prominent, trend is one that has changed little over the centuries. Children’s books are full of doodles, inscriptions, and signatures. Cathrine Edwardson’s well-loved copy of Divine Songs for Children shows how even in the eighteenth century, children made books their own by practicing their signatures or drawing pictures in the blank spaces.

Inscriptions like Cathrine’s are not uncommon finds, although it varies widely as to what the children write and where they write it – which makes each book new and unique.

The other trend is one that has changed significantly from the origin of British children’s literature to today.

The bulk of the museum’s special book collection consists of books published just before or in the decades immediately after the beginning of the nineteenth century. Many of them have quite descriptive titles such as The History of Tommy Playlove and Jacky Lovebook, Wherein Is Shewn the Superiority of Virtue Over Vice, However Dignified by Birth or Fortune (1819), or The Sister’s Gift, or The Naughty Boy Reformed, Published for the Advantage of the Rising Generation (1812). These heavily didactic tales seem like a far stretch from the whimsical stories I heard as a child, which has to do with how children’s literature progressed as a genre.

The idea of “children’s literature” emerged in Britain in the mid-eighteenth century, when means for printing and publishing became more widespread. The early generations of children’s writers tended to create moral stories in which good behavior was rewarded and bad behavior was severely punished. These stories were influenced largely by Enlightenment philosopher John Locke, who believed a child is a blank slate (“tabula rasa”) with an innocent mind on which needed to be written the morals of society. The purpose of children’s literature, then, was to instruct children in exactly what those morals were

MC.2019.080 – magnified preface to The Girl’s Own Book by Lydia Child

Additionally, parents were the ones choosing what books their children read. Often a preface is addressed to them, instead of the children for whom the book was written. They tend to explain to the parents how the book will be useful for the child’s growth and learning.

These books are commonly inscribed with notes such as that in Evenings at Home; or the Juvenile Budget Opened: Consisting of A Variety of Miscellaneous Pieces for the Instruction and Amusement of Young Persons by early children’s writer Anna Barbauld and her brother John Aikin, which indicates that the book was a gift to a little girl “from her affectionate Father.” Thus, many of these books are a better indication of what parents would like to have their children read than what children themselves would want to read.

MC.2019.068 – inscription inside of Evenings at Home by Dr. Aikin and Mrs. Barbauld

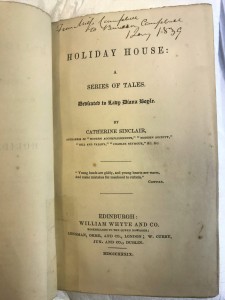

In 1839, Edinburgh-born author Catherine Sinclair challenged these norms in children’s literature by producing a story that depicted children as mischievous – not passive followers of moral instruction – in her book Holiday House. The Museum of Childhood’s special book collection features a first edition, printed by William Whyte and Co. in Edinburgh.

This work was one of the first children’s stories to depict children as, well, children! Her preface states that she wishes to recall the days when children were noisy and frolicsome, when they had individual characters that allowed for eccentricities.

Holiday House foreshadowed the next trend in children’s literature, which began in the 1860s with the publication of children’s stories like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll and The Water-Babies by Charles Kingsley. These authors traded explicit morality for imagination and fantasy. They created children’s stories that the children would choose for themselves.

MC.2019.010 – title page of Sinclair’s Holiday House

This new and so-called “golden age of children’s literature” ushered in by Carroll and Kingsley falls outside the scope of the Museum of Childhood’s special book collection (which consists of items from 1850 and earlier), and thus my own area of expertise, but the Alice books and other fantastical stories are still familiar from my own experiences growing up.

Although the early stories themselves may be less exciting to children today, those in the special book collection at the Museum of Childhood are an important record of the changes that children’s literature has faced through the centuries. They also represent the children themselves, who drew pictures and inscribed their names in their books – much like any child of our own time would.

Kathryn Downing

MSc Book History and Material Culture, University of Edinburgh

For Further Reading:

International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature. Second Edition. Edited by Peter Hunt. London: Routledge, 2004. Vols. 1-2.

McGavock, Karen L. “Agents of Reform?: Children’s Literature and Philosophy.” Philosophia 35 (2007): 129-143. doi: 10.1007/s11406-007-9048-x.

Darton, Frederick Joseph Harvey. Children’s Books in England: Five Centuries of Social Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139060752.